Hardware ID and DRM: A naïve approach to anti-piracy

I was introduced to hardware ID (“hwid”) a number of times from people who make cheats for online video games, and after doing some research, it has become apparent that hwid is a flawed way to secure your program. Before we get started, this post is only about online DRM. For the people who are making addons or modifications for online games, requiring an internet connection is not a problem because anyone using their software would have to be online in the first place. Software such as Microsoft Word is different, because users expect it to function offline. Offline or mixed-use software has little to no use for hardware identifiers.

What is hwid?

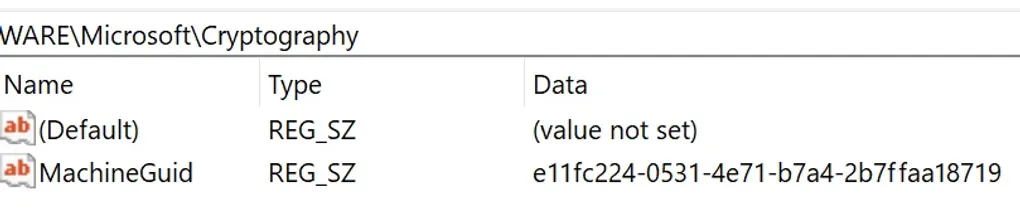

From what I can tell, operating systems like Windows generate a unique hardware-based identification key when they are installed. Windows stores this key in the registry and allows any program to access it. Any change to your hardware, even something like moving your RAM into different physical slots, can force this identifier to change. Software programs may track your hardware ID as part of their licensing scheme, so they can make sure their program isn’t being used on multiple machines.

There are other identifiers that can be used in place of the traditional registry hwid token, such as the CPU ID, hard drive serial number, and the computer’s network name. However, multi CPU systems (rare) may not work well with a CPU ID system. Multiple hard drive systems (fairly common, especially when you count SSDs) can make a serial number check fail, and network names are the easiest to change or spoof when the user’s computer is not part of a large organization.

How do I correctly implement a hwid check?

There are a lot of language-specific pitfalls that you should research online, especially if you’re using a low-level language like C++. This post does not address all of those problems.

Most implementations of hardware identification, especially when not done by a professional, fall flat on their face. Users can edit their hardware ID or use a specialized program to spoof the various factors used to identify their computer. These methods are incredibly effective at tricking most programs into believing that the user is on the same computer to which they originally registered the software. An advanced implementation of a hardware ID checker could act like an Antivirus, by looking for spoofing programs that might be running, or evidence of tampering. However, making “antivirus” DRM software is a drain on development resources and is widely considered to be extremely intrusive.

A smarter approach would be to get each of these hardware-linked identifiers, and check to make sure that most match your records. This method is more robust, but the fewer matches you require is, the easier it is to trick your identification system.

I would personally recommend checking the CPU ID, total drive space, network name, MAC address, and screen resolution. At least three of those identifiers must match, otherwise the user should not be allowed to proceed. This should strike a balance between convenience and security.

Common pitfalls

- You put your database credentials in the software, and all further checks are done directly on the user’s machine. Oops! Someone decompiled the code and now has total access to your database, and this is devastating even if the access is read only.

- The authentication request is done without encryption. Oops! Someone knows what response the program is expecting back, and has now made a secondary program that spoofs the server and allows anyone to use your software.

- The hwid authentication is done with only one factor. Oops! Someone did

winkey + Rand typed in “regedit”. Now any machine can pass your hwid check. Or, you only checked their hard drive serial number and a user installed a new hard drive. Now they’re locked out. - IP address tracking is used instead of hwid. Legitimate users can’t use a VPN, and they run into problems if/when they’re assigned a new IP by their service provider.

- No hwid checks are performed, and the sign in process has nothing to prevent duplicate sign ins. Oops! 20 people now share one username/password combo, and they’re all using your software for free. Maybe you should have a cool down on sign in attempts per account?

- The program is not obfuscated in any way. Oops! Everyone can see every little mistake you made, and one of them completely undermines your security. An attacker finds the mistake and spends less than 10 minutes patching the instruction. Worse, the important parts of your program are almost completely visible to the world and someone else decides to make a replica of your program available for free.

Conclusion

No solution is perfect. DRM is just like all types of security in the sense that it lives in tension with convenience. If you want your program to work offline, then you have to store a file somewhere or use very complicated methods to burn your DRM into your installer. If you want to avoid hardware id, then you need a rate limiter on the sign in process, or an ongoing check to monitor in case anyone shares their account. The best solution is a little bit of DRM sprinkled in, just enough to protect legitimate sales without inflaming the inevitable piracy. Pirates will always be out there, but you can still profit off of your hard work. Good luck.